Assuming no last-minute surprises, it looks like we may be getting a debt ceiling deal within the US, which suggests you have to be ready to get overwhelmed by monetary commentators’ takes about ‘liquidity.’

The very unnuanced story goes like this: The federal government must rebuild its Treasury Common Account (TGA) buffer on the Fed, so it points bonds and it drains ‘liquidity’ from the ‘system.’

And right here, I can image you guys pondering: What the heck does that imply? And is it true?

Financial mechanics are finest understood by the usage of good outdated T-accounting.

In our stylized mannequin, we are going to assume 5 gamers (authorities, Fed, business banks, cash market funds, and households) and mimic every financial transaction – colours will provide help to “observe the circulate of cash.”

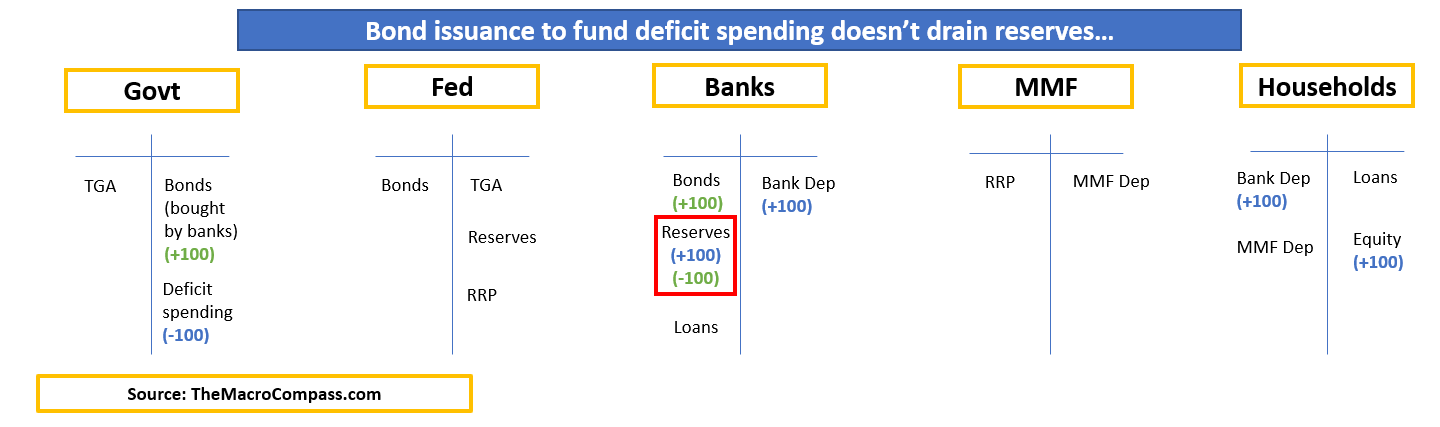

Earlier than we go to the post-debt-ceiling TGA, rebuild, let’s begin with bond issuance to fund deficit spending.

BLUE: The federal government spends $100 (deficit spending), and it injects web value into the non-public sector (family’s fairness) and so households now have $100 extra financial institution deposits. These financial institution deposits find yourself as a legal responsibility for banks, and the corresponding improve in belongings is a lift of $100 in financial institution reserves.

GREEN: The federal government “has” to concern $100 in bonds to “fund” its deficit spending, and banks use a few of their elevated reserves to purchase $100 in bonds.

There is no such thing as a discount in financial institution reserves when the federal government points bond to ‘fund’ deficit spending.

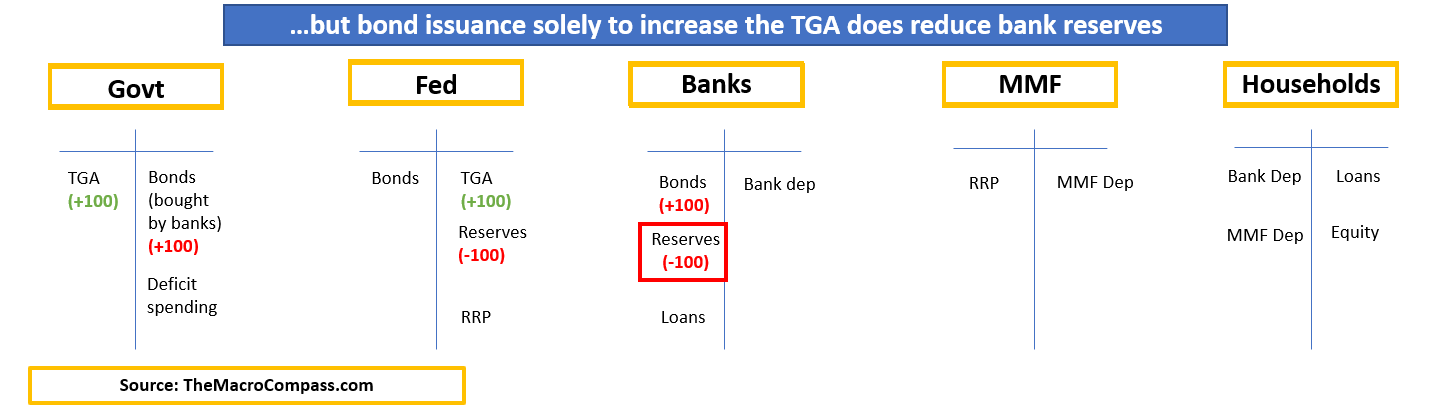

However what occurs as a substitute if the federal government points bonds solely to refill its Treasury Common Account as in a typical post-debt-ceiling-deal interval?

RED: The federal government points $100 in bonds with out spending something in the actual financial system, and banks have to soak up the brand new bond issuance by depleting current financial institution reserves ($ -100).

GREEN: The federal government refills its Treasury Common Account (TGA), and that’s mirrored within the composition of the Fed liabilities: TGA up $100, financial institution reserves down $100.

That is how a TGA rebuild drains ‘liquidity’ (e.g., reserves) from the monetary system.

If the federal government points bonds with out spending actual financial system cash and banks/non-public sector should take up the brand new issuance with none recent new sources, financial institution reserves take the brunt.

However why are financial institution reserves known as ‘liquidity’ within the first place?

Financial institution reserves are cash for banks: They use reserves to transact towards one another and with the Fed, and you may consider them because the lubricant of the financial mechanics pipes – the extra reserves on the market, ceteris paribus, the better for banks to interact in repo markets and supply liquidity to market individuals.

Reserves are additionally a part of banks’ high-quality liquid belongings (HQLA), and therefore an even bigger reserve stability would possibly encourage banks to take extra dangers of their liquidity portfolio, as an example, by shopping for company bonds – this compresses credit score spreads and enacts a extra favorable atmosphere for fairness traders.

Quite the opposite, fewer reserves are sometimes related to banks taking a extra defensive funding stance and offering markets with much less liquidity.

So, is it as straightforward as saying that the TGA rebuild will for certain drain liquidity from the monetary system?

We should wait and see.

***

This text was initially printed on The Macro Compass. Come be part of this vibrant group of macro traders, asset allocators, and hedge funds – try which subscription tier fits you essentially the most utilizing this hyperlink.

Adblock take a look at (Why?)